Conditions are restrictions that are imposed on an accused person for the pre-trial period, and they can last from several weeks to months in duration. As the first component of the Policing Indigenous Communities Initiative, the Conditions Project addresses the disproportionate impact of conditions of pre-trial release on Indigenous persons charged with offences, with a particular emphasis on people living in rural and remote communities.

The consequences of multiple arrests, charges, and court appearances for breach of conditions creates what researchers call a “revolving door” [1] where marginalized people move in and out of the criminal justice system. Addressing the impacts of conditions is a key point of intervention to disrupt this cyclical process.

Conditions can include a number of restrictions such as where an accused person can go (also known as “red zones”), who they can contact, restrictions on drug and alcohol use, and curfews. They can be issued by a police officer on arrest or by a justice or judge at a bail hearing. An accused person who fails to comply with their conditions may be charged with additional offences under the Criminal Code, [2] and may be arrested and held in custody until trial for breaching their conditions.

The law is not supposed to work this way.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms [3](the “Charter”)guarantees that persons charged with offences have the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty and the right not to be denied reasonable bail without just cause. Despite these constitutional guarantees, there is evidence that the police and the courts are imposing conditions on accused people that are contrary to the spirit of the law.

Research has shown that spatial conditions of release, also known as red zones, are “regularly imposed contrary to the provisions of the Criminal Code and fail to meet the goals set by the law.”[4] Researchers who study Canada’s bail system have concluded that, “the bail system is operating in a manner that is contrary to the spirit – and, at times, the letter – of the law.”[5]

We know that Indigenous people are significantly over-represented in the rates of incarceration across Canada. We suspect that this over-representation can be traced back to unreasonable conditions of pre-trial release, where Indigenous people are caught in the “revolving door” of the criminal justice system for failure to comply with these conditions.

“Nearly every issue highlighted… – over-policing, routine adjournments, the overuse of numerous bail conditions, abstention and treatment conditions, difficulties with surety requirements, and the particular challenges faced by individuals detained in remote communities – disproportionately impacts Aboriginal people.”[6]

What do we plan to do?

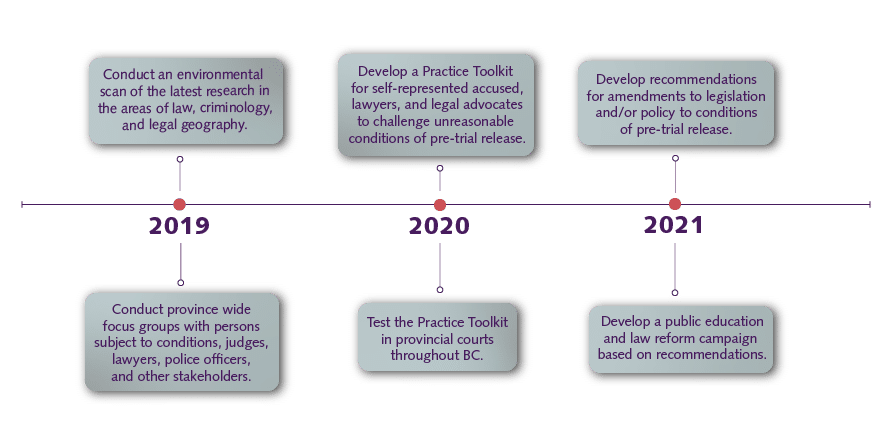

The Conditions Project is a three-year project beginning in 2019. We will start by conducting our own research in collaboration with our community partners. Then, we will develop and deliver a Practice Toolkit for use by self-represented accused, lawyers, and legal advocates to challenge unreasonable conditions of pre-trial release in court. Finally, we will develop recommendations for amendments to legislation and/or policy to address the problem, followed by a public education and law reform campaign.

We will be updating this page periodically as the project progresses. If you want to learn more about conditions of pre-trial release click here.

Notes

[1] See Canadian Civil Liberties Association et al. ‘Set Up to Fail: Bail and the Revolving Door of Pre-trial Detention’, (2014).

[2] Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c. C-46, s. 145(3): Failure to comply with conditions on undertaking or recognisance.

[3] The Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c. 11 (the “Charter”).

[4] Sylvestre, Marie-Eve, et al, ibid, at p. 81.

[5] Canadian Civil Liberties Association, et al, ibid, at p. 1.

[6] Canadian Civil Liberties Association, et al, ibid, at p. 77.