What are your rights?

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms[1] (the “Charter”) guarantees legal rights for persons charged with an offence. Section 7 of the Charter states:

“Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.”

When a person is arrested and charged with a criminal offence, their right to liberty is interfered with by the state. The state can only interfere with a person’s liberty rights in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice. These principles are based in the fundamental tenants of our justice system[2], such as the right to silence and the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty.

In addition to the rights guaranteed in Section 7, Section 11 of the Charter guarantees the procedural rights of a person charged with a criminal offence. Sections 11(d) and (e) guarantee that any person charged with an offence has the right:

(d) to be presumed innocent until proven guilty according to law in a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal; and

(e) not to be denied reasonable bail without just cause.

[1] The Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c. 11 (the “Charter”).

[2] See Re B.C. Motor Vehicle Act, [1985] 2 SCR 486.

What is pre-trial release

A person arrested and charged with an offence may not go to trial for weeks or months after their arrest. During that time, the accused is either released into the community or held in custody to await trial. Release into the community is known as “pre-trial release” or “bail”. Pre-trial release may be granted by a police officer on arrest or by a justice or judge at a hearing following an arrest.

Pre-trial release by a police officer

After a person is arrested for an offence, a police officer can either release the accused with conditions or hold the accused in custody to appear before a justice or judge within 24 hours. If the accused is released, the officer may require that the accused sign an undertaking (i.e. Form 11.1).[1] An undertaking, sometimes called “A Promise to Appear”, is a written promise given by an accused person to appear in court at a stated time and place. An undertaking may also include a promise to comply with other conditions.

For example:

- Stay within a specific city or jurisdiction

- Notify the police of any change in address or employment

- Stay away from the victim

- Surrender passport to police

- No possession of firearms or weapons

- Report to police or court as specified by the police

- No use of alcohol or drugs

- Follow any other conditions that the police consider necessary to ensure the safety of victims and witnesses (see s. 499).

If the accused refuses to sign the undertaking, they will be held in custody until they appear before a justice or judge (within 24 hours). The justice or judge will decide whether the accused will be released with conditions or continue to be held in custody to await trial.

[1] Criminal Code, ibid, Schedule [to Part XXVII], Form 11.1: Undertaking Given to a Peace Officer or Officer in Charge.

Pre-trial release by a justice or judge

When a person charged with an offence[1] is taken before a justice or judge (within 24 hours of arrest), the justice or judge must order that the accused be released onan undertaking or bail with or without conditions unless the prosecutor shows cause why the detention of the accused in custody is justified.[2] Bail cannot be denied unless there is a “substantial likelihood” that the accused will commit a criminal offence while on bail or will interfere with the administration of justice.[3] If the accused is released on bail, conditions can include: Report to a bail supervisor Stay within a specific city or jurisdiction Notify the police of any change in address or employment Stay away from the victim Surrender the accused’s passport to police Follow any other conditions that the judge considers necessary to ensure the safety of the victims and witnesses Follow any other conditions that the judge considers reasonable (s. 515) If the accused refuses to agree to the bail conditions, they will be held in custody to await trial. [1] Other than offences listed under s. 469 of the Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c. C-46: i.e. murder, etc. [2] Criminal Code, ibid, s. 515(1). [3] R v. Morales, 1992 CanLII 53 (SCC).

What is the impact of conditions of pre-trial release on persons charged with offences?

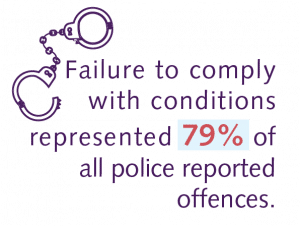

When a person charged with an offence does not follow (or “breaches”) their conditions of pre-trial release, the accused can be charged with a new offence for failure to comply with conditions under Section 145(3) of the Criminal Code. Failure to comply with conditions is referred to as an “offence against the administration of law and justice” or an “administration of justice” offence.[1]

While on pre-trial release or bail, an accused with unreasonable conditions may receive many charges for failures to comply. One study showed that, “even when the original charge is withdrawn or dismissed, the Crown will frequently still pursue a conviction for charges of failure to comply with a bail order.”[2] Another study found that, “[I]n 75% of cases,[administration of justice offences] were the most serious offences involved in the incident.”[3] What these studies demonstrate is that the courts and the criminal justice system are overridden by administration of justice offences. As one “Legal Actor” put it in one of the studies:

“I have seen most stuff coming through these courts these days being failing to comply and breaches, and I don’t understand. Where did all the real criminals go? Why isn’t everybody charged with new offences? Because most of what we see on a day to day basis anymore are failures to comply and breaches.”[4]

Many accused agree to conditions without question because the alternative is being held in custody for weeks or months to await trial. This means that accused people frequently agree to conditions that are highly restrictive or unrelated to their original charge.

“Accused will agree to almost anything to avoid returning to detention. Lengthy waits in custody for bail hearings may exacerbate this pressure.”[6]

Spending any amount of time in jail, even overnight, can be dangerous and have serious repercussions for an accused personal life.

“Even a few days in detention can mean emergency child care arrangements, lost income, a lost job or skipped medication.”[7]

While the impact of being held in custody may seriously impact a person’s life, unreasonable conditions of pre-trial release may be equally impactful, especially for marginalized people.

[1] See Criminal Code, ibid, Part IV.

[2] Canadian Civil Liberties, et al, ibid, at p. 2.

[3] Sylvestre, Marie-Eve, et al, at p. 29.

[4] Sylvestre, Marie-Eve, et al, at p. 61.

[5] Sylvestre, Marie-Eve, et al. ‘Red Zones and Other Spatial Conditions Imposed on Marginalized People in Vancouver’, (2017), at p. 3.

[6] Canadian Civil Liberties Association, et al, at p. 30.

[7] Canadian Civil Liberties Association, et al, ibid, at p. 9.

Impact of conditions on social support systems

Spatial conditions (or “red zones”) are areas where an accused may not enter. Generally, red zones are selected based on where the alleged offence took place. Spatial conditions may isolate the accused from their social support systems, including their homes, their families, and essential social services. For many marginalized people, red zones can prevent access to essential services. In accessing these services, accused run the risk of re-arrest and addition charges for failure to comply with conditions.

“Red zones force [those on supervision] to choose between compliance with order and meeting basic health safety needs when the red zone cuts them off from accessing the services and community connections that they rely upon.”[1]

In Pivot Legal Society’s Full Report: Project Inclusion, one of the participants, relayed her experience with red zones:

“It didn’t make sense, my bank was there, my home was there, my probation was there, my doctor was there, like come on guys! All of Hastings Street? Hello! My whole life is there! They’re going to arrest you every time you want to go home?”[2] – Lisa

[1] Bennett & Larkin. ‘Full Report: Project Inclusion’, (2018), at p. 96.

[2] Bennett & Larkin, ibid, at p. 71.

Impact of conditions on addiction

In addition to spatial conditions, conditions that restrict an accused from using drugs and alcohol are common. Conditions that require abstinence are especially problematic for persons living with addiction, in that abstinence conditions put an accused into a position where they must choose between the threat of severe withdrawal symptoms and the threat of failure to comply charges on their criminal record. Spatial and abstinence conditions are related, in that an accused’s drug supply may be within the red zone.

“The court will give you a red zone so you can’t come into this area. But I’m an addict. They sell drugs in that area. So in order for me to get drugs, I have to go to that area. So even if the court tells me not to I still go.” – Samuel [1]

[1] Sylvestre, Marie-Eve, et al, ibid, at p. 67.

Impact of Conditions on Indigenous people

While there is some research on the disproportionate impact of conditions of pre-trial release on marginalized people in urban areas, generally, there is little research on that impact on Indigenous people in rural and remote communities. This is the population we will focus on with the Conditions Project.

We know that Indigenous people are significantly over-represented in the rates of incarceration across Canada. We suspect that this over-representation can be traced back to unreasonable conditions of pre-trial release, where Indigenous accused are caught in the “revolving door” of the criminal justice system for failure to comply with these conditions.

In the landmark case of R v. Gladue, the Supreme Court of Canada traces the over-representation of Indigenous people in prison back to the systemic discrimination that results in poverty and substance use. The Court also notes that Indigenous accused are more likely than non-Indigenous accused to be denied bail:

“The unbalanced ratio of imprisonment for aboriginal offenders flows from a number of sources, including poverty, substance abuse, lack of education, and the lack of employment opportunities for aboriginal people. It arises also from bias against aboriginal people and from an unfortunate institutional approach that is more inclined to refuse bail and to impose more and longer prison terms for aboriginal offenders.”[1]

The research conducted on the impact of conditions of pre-trial release on Indigenous people demonstrates that accused face barriers with respect to bail. Because some bail orders require a person to post a bond, some Indigenous accused are not able to be released on bail:

“On Aboriginal reserves, few, if any, community members own property. This can be problematic as bail orders generally have a financial component.”[2]

In addition, court resources for remote communities are limited. Accused awaiting a bail hearing may be flown into another jurisdiction, which can take longer than those who have bail courts readily available in their community:

“For accused from remote communities, time in custody may be longer as it may take up to a week to be transported to the nearest provincial detention centre.”[3]

Based on the limited research available, it is clear that the question of whether conditions of pre-trial release disproportionately impact Indigenous people needs to be addressed.

“Nearly every issue highlighted… – over-policing, routine adjournments, the overuse of numerous bail conditions, abstention and treatment conditions, difficulties with surety requirements, and the particular challenges faced by individuals detained in remote communities – disproportionately impacts Aboriginal people.”[4]

[1] R v. Gladue, 1999 CanLii 679 (SCC), at para 65.

[2] Canadian Civil Liberties Association, et al, ibid, at p. 41.

[3] Canadian Civil Liberties Association, et al, ibid, at p. 22.

[4] Canadian Civil Liberties Association, et al, ibid, at p. 77.